Art Beat Goes On For Emma Astrike-Davis and Family

By Al Daniel

At 11 years going on 12 this spring, Art for Hospice is nearly as old as its founder, Emma Astrike-Davis, was at its inception. And like an Adolescent student at the Montessori Community School, it has built a vast and varied network of friends, become precociously cultured, and, in most fundamental areas, proved itself independent of its parent.

That last detail is especially important for Astrike-Davis as she continues her education at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. While she still wears, by her count, a seven-billed hat for her charity, she is on pace to obtain her MD in 2022. Before that, she has a host of objectives to chase as part of her studies.

But the organization — which started growing in earnest on the MCS campus and whose straightforward name tells the story of bringing lively original imagery to homes for the elderly and ailing — has ample company to thrive with. Monetary and artistic contributions are produced and distributed in 13 states and on three continents, going as far as Argentina, England, and Honduras.

“Art for Hospice is becoming more and more self-sufficient,” Astrike-Davis said, “as students and art teachers at the participating programs take on more ownership of their projects each year. My plan is to continue to facilitate their work remotely by fundraising and providing supplies.”

To date, the founder has been “president/board chairperson, as well as spokesperson, photographer, webmaster, fundraiser, and, on occasion, artist.” Those commitments have left little time, if any, to savor the charity’s quantifiable achievements. As it gets to be half its founder’s age, and subsequently less, Art for Hospice has surpassed $10,000 in donations and 5,000 pieces of artwork.

“The organization has grown and continued to thrive far more than I envisioned when I was 12,” said Astrike-Davis. Explaining its traction, she added, “Compassion is a ubiquitous need around the world, and is something we are capable of giving at any age.”

Her parents, Nancy Astrike and Joan Davis, let her know about her capacity for compassion early enough. When the household was the three of them, they volunteered at neighborhood cleanups and brought Emma’s cousin along to play the piano at a nursing home.

After she enrolled at MCS, Astrike-Davis says, family philanthropy began to “intertwine naturally” with Earth Day projects and school-sanctioned visits to the Ronald McDonald House and assisted-living homes. That crisscross emanated all the more when her guide, Michelle Reader, brought her choir to carol for nursing-home residents over Christmas break.

When Astrike-Davis was in Upper Elementary, her calling rang louder, as the purpose of nursing facilities hit closer to home. Her great-grandmother left the familiar confines of her longtime, self-built residence and moved into Durham’s Brian Center.

The move came with a trade-off, as she now lived closer to her relatives. Still, her great-granddaughter realized the new place needed a personal touch. The easy fix was hanging homemade paintings on the wall.

The artwork’s spiritual impact was instantly evident, but so was the comparative lack of flair in other people’s rooms. When Astrike-Davis observed this discrepancy, her first beneficiary offered a straightforward statement of encouragement.

“Well, you can do something about that.”

“It certainly seemed like a daunting task for one artist,” Astrike-Davis recalls. But at MCS, she soon got a chance to awaken the creative and compassionate streaks of hundreds of hidden artists.

In May 2008, as a sixth-year student, Astrike-Davis was appointed honorary head of school for a day. Once she reined in her knee-jerk excitement and squared away the conventional kid-like orders of business, she plugged the concept of Art for Hospice.

“Dave Carman (previous head of school) was incredibly receptive and supportive of my endeavor,” she said.

Ahead of that revolutionary day, Astrike-Davis enlisted hospice social workers to explain what the project would mean to their residents. She also cut a deal with a local art supplier to equip everyone with blank canvases. Through that motivation and those means, the student body and staff combined for 25 works.

Art for Hospice’s website quotes Carman as reflecting, “Many other kids here, who watched what took place and saw that it was satisfying, will look for the chance to make the same kind of difference when their turn comes. As it will.”

Although he did not live long enough to see how prophetic he was, Carman poignantly benefited from the charity himself. Three years after Astrike-Davis left MCS, Carman faced a terminal diagnosis, and the two met for tea in his hospice.

“I will never forget the expression on his face as this eloquent man struggled to say ‘Thank you’ for the piece of art that his own kindergarten class had made for him,” Astrike-Davis said.

None other than Emma’s brother, Evan Astrike-Davis, was part of that Primary group. After contributing to the inaugural Art for Hospice project with his grandmother’s assistance, Evan wasted little time grasping his sister’s foundation’s meaning.

“There wasn’t anything any of us could do to help (Carman),” he recalled. “But somehow painting a picture for him gave us a sense of purpose.”

By then, Art for Hospice had asserted its appeal beyond the MCS community. Within two years of its conception, through a $600 grant from the town of Cary, it garnered 501(c)3 status and an online presence.

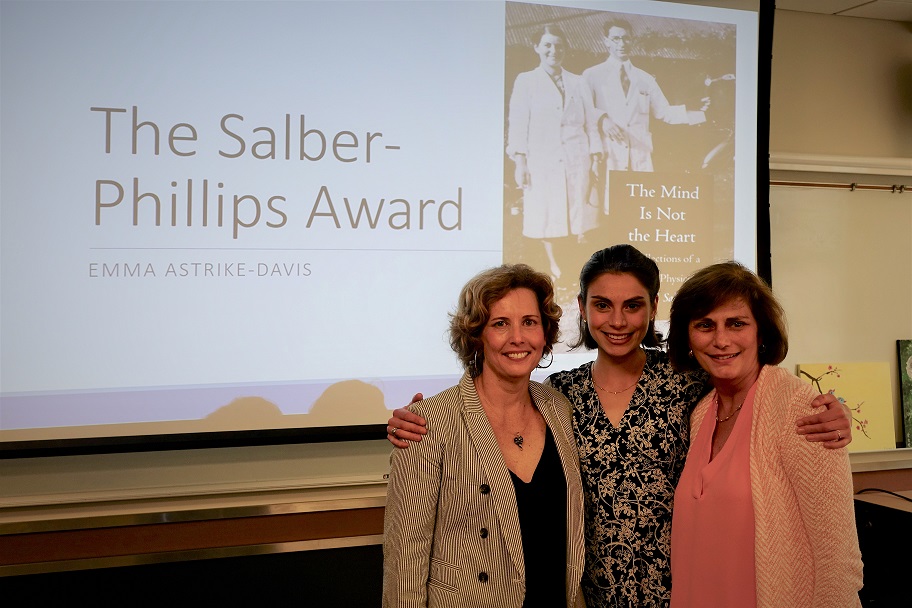

As she kept fostering the foundation in high school, Astrike-Davis was honored at the 2012 AFP Triangle NPD Awards (nominated by the Hospice for Wake County) and nationally by the Prudential Spirit of Community. She is quick to credit her former Mustang peers, particularly Marie-Caroline Finke and Kaitlyn Reed, for propping up the project and spreading its spirit across the Research Triangle.

Back on Pope Road, which she still visited to lend artistic direction and coach Girls on the Run, her brother kept Art for Hospice in sight and in mind. By 2015, the year he transitioned from Lower to Upper Elementary, he was ready to launch a related initiative.

During one December round of art distribution, Evan took note of a resident’s remark: “People always come at Christmas, but they just forget about us the rest of the year.” He pledged to do something about that and sought out another occasion to return.

Together with his peers in Cub Scout Pack 495, Evan established Scouts with HeART, gearing its mission toward lighthearted Valentine’s Day cards. To make their first impression that February, 20 scouts used their full hour-long meeting to produce as many greetings as possible. They then delivered more than 100 to various nursing-home and hospice residents.

“Along the way,” Evan said, “I have learned that you don’t have to have a reason to visit a nursing home, but when you have a painting or a card or something to share it does help to break the ice. The real point is to give your time and visit people.”

The firsthand delivery, Emma says, is key in that it “adds the dimension of interaction. I think that it is wonderful for participants in Art for Hospice to meet the recipients of their artwork, and Scouts with HeART facilitates this interaction. The Cub Scouts and many Girl Scout troops have embraced the concept and expanded upon its mission.”

For the founder, how far they are taking that mission is getting gratifyingly harder to track. But miles and money, she says, take a backseat to emotional value.

“Success we measure not with numbers, but in the smiles (and tears) of the recipients.”

In another testament to Art for Hospice’s breadth, whether eyes are lighting up or welling up, more success stories are requiring worth of mouth to return to the epicenter. Astrike-Davis was reminded of her original purpose when a Veterans Affairs volunteer relayed the news of one Army veteran who received a painting and literally held on to it through his final days. His loved ones subsequently inherited the art, keeping it on prominent display.

Of that veteran she never knew and the head of school she knew well, Astrike-Davis cites a crucial common thread. “A simple picture brought both of these men comfort and pride — the very things my great-grandmother wanted me to provide to others in need.”

As she inches deeper into adulthood, Astrike-Davis aims to add a more tangible means of delivering comfort to her repertoire. At UNC, she is coming off an aging research fellowship and hopes to attend this spring’s American Geriatrics Society conference.

Regardless of what that subtracts from her involvement in Art for Hospice, she takes her own measure of security in its network, especially given the way Evan emulates her.

Besides running Scouts with HeART, which he admits may not last much longer now that he has aged out of the Scouts, Evan has ascended to the parent company’s vice presidency. He has also taken the requisite painstaking steps to join forces with his current art teacher at Cary Academy and phase Art for Hospice in there.

“We’ll see if he wants to take on the presidency next election season!” Emma said.